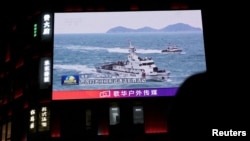

With jets, warships, and a bombardment of propaganda, China simulated attacks and maritime blockades around Taiwan, in what Beijing called a warning after the island’s president labeled China “a foreign hostile force.”

The two-day war games around Taiwan that included long-range, live-fire drills came to an end on April 2, the Chinese military’s Eastern Theater Command said, but the unannounced drills mark an escalation from Beijing towards the self-governing island, which China has long threatened to invade and annex if it refuses to peacefully accept unification.

While previous Chinese drills have sought to test Taipei's response times to an incursion, Beijing says this week's exercises -- called “Strait Thunder” -- were focused on its ability to strike key targets such as ports and energy facilities on the island. In a statement, the Chinese military said that the drills tested the troops' "integrated joint operations capabilities" as a coordinated seizure of the sea and airspace around Taiwan, blockading Taiwanese sea lanes, and launching attacks against sea and ground targets.

That’s noteworthy as it represents the variety of ways that a crisis could develop around Taiwan and comes as Beijing looks to send an implicit message to US President Donald Trump and his administration that China is determined to put the island of 23 million under its authority one way or another.

Taiwanese policymakers must contend not only with the potential threat of an outright invasion but also with the possibility of China launching a blockade to choke off trade and supplies until the island submits to Beijing. Another scenario would be what security analysts called a quarantine, which means China could restrict air and maritime traffic into Taiwan and tighten its control over the flow of commerce using its coast guard and other law-enforcement forces, rather than its military.

Such a move could lead to difficulties in mobilizing international support for Taiwan and leave the island vulnerable before a response from Taipei’s partners could be launched.

The Strait Thunder drills were located in the middle and southern parts of the Taiwan strait -- a vital artery for global shipping -- and were clearly simulating for these scenarios. Taiwan imports nearly all of its energy supply and relies heavily on food imports, meaning in the event of a war, a blockade or even quarantine could paralyze the island.

Beijing was keen to press this advantage with its war games, but it also turned to tough rhetoric against the island’s leaders and messaging geared towards residents about Beijing’s military superiority. As China’s military announced the drills, it also released posters declaring that it was “closing in” on “Taiwan separatists,” as well as a series of personal attacks on Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te.

One animation depicted Lai as a poisonous “parasite” trying to hijack Taiwan -- until he ultimately met a fiery end.

Lai is a popular target for Beijing’s messaging campaigns and China’s Taiwan Affairs Office called the drills “severe punishment” for his “rampant provocation” with recent actions that “exposed his ugly side of being anti-peace, anti-exchange, anti-democracy, and anti-humanity.” Those actions refer to a March 13 speech where Lai laid out a coordinated roadmap for how to push back against Beijing and labelled China “a foreign hostile force.”

"China has been taking advantage of democratic Taiwan's freedom, diversity, and openness to recruit gangs, the media, commentators, political parties, and even active-duty and retired members of the armed forces and police to carry out actions to divide, destroy, and subvert us from within," Lai said at the time.

That speech followed months of escalating rhetoric from Beijing, as well as a series of incidents, from espionage cases to vessels caught trying to sever undersea data cables running off the coast of Taiwan. Lai has also looked to maintain US support for Taiwan during Trump’s term, including by promising to raise its military spending to more than 3 percent of the island’s economic output this year.

The latest Chinese exercises also follow a visit to the region by US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth last week and a Washington Post report citing an internal Pentagon memo signed by him calling for the US military to prioritize deterring a Chinese takeover of Taiwan.

“China is the Department’s sole pacing threat, and denial of a Chinese fait accompli seizure of Taiwan -- while simultaneously defending the US homeland is the Department’s sole pacing scenario,” Hegseth wrote in the memo.

Trump has yet to detail his policy toward Taiwan and has said he won't state whether he would send US forces to defend it in a crisis or not, but with moves like the recent war games, Beijing is looking to probe for how Washington may react and show the Trump administration that its red lines around Taiwan aren’t going away.